Fr Thomas O’Gorman SJ has lived through exciting times. He came of age after World War II in New York City, and joined the novitiate before turning 18. He was a young Jesuit missionary when he experienced the awakening of Filipino nationalism; as a young priest witnessed the racial divide in his own country. He studied in Rome during the era of Vatican II, and saw first-hand the rule of Martial Law in the Philippines. In Rome, he pronounced his Final Vows before the Society’s new Superior General, Fr Pedro Arrupe SJ. Another Superior General, and fellow missionary to Asia, Fr Adolfo Nicolás SJ, was his contemporary and friend. Gratitude and obedience keep him going after all these years.

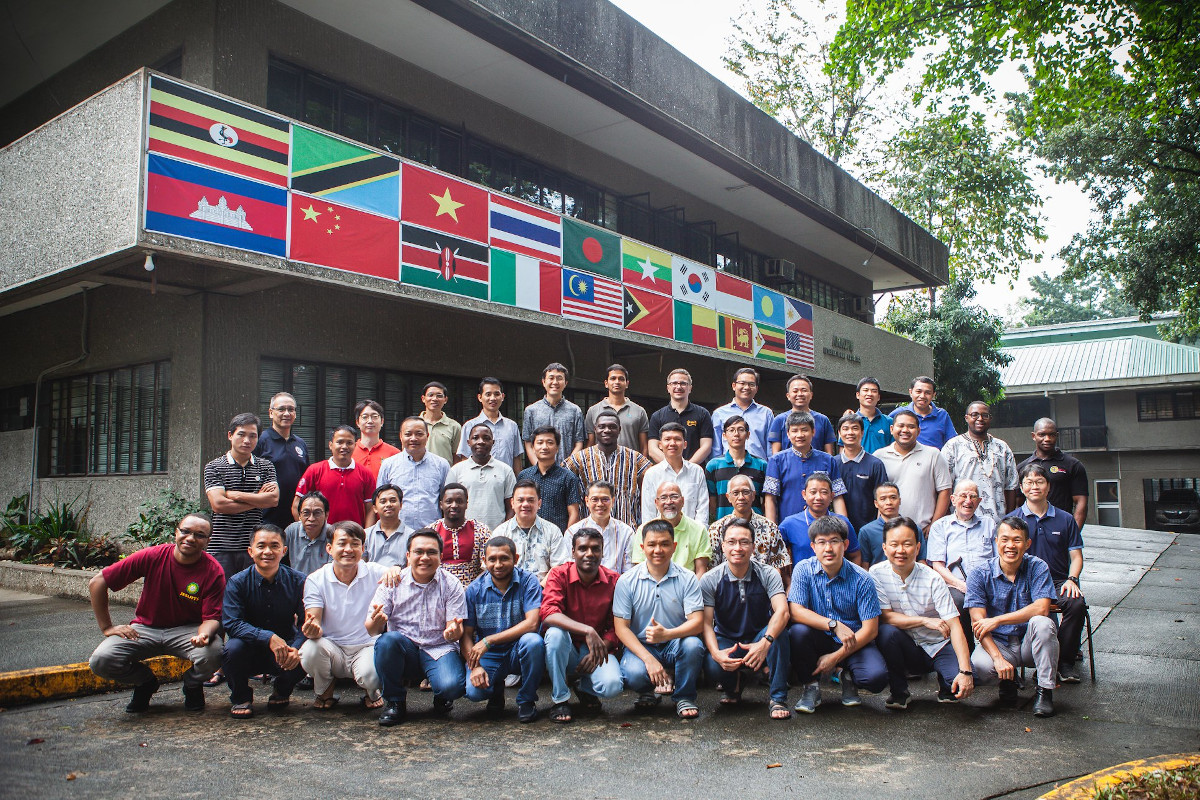

He jokingly calls himself the “grandpa” of his community at Arrupe International Residence, Manila. Surrounded mostly by scholastics half his age, Fr O’Gorman appreciates the care they give him. He turns 88 this year and celebrates his 70th year as a Jesuit on 30 July. “It was 1950 when I entered. I was 17!” he says. The boy from New York had a “simple Catholic life” with a brother who wanted to be a priest, an uncle who was a priest, and a sister who wanted to be a nun. “People would ask me, do you want to be like your brother? No! But I didn’t know what I wanted to be,” he admits.

At Xavier High School in New York City, joining the Jesuits was practically de rigueur for the students. “In high school, I was constantly asking myself what do I really want to be? I wasn’t sure.” Working for the school paper, young Tom became friends with a Jesuit, Fr Taylor. “One day, we were having a recollection. Fr Taylor was kneeling down before giving a talk. And I said to myself–because I was constantly asking the Lord, help me to see what I really want to be. I saw this man who I really admired, we were good friends, and I said why do I say that I don’t want to be like him? What would happen if I want to be like him! And suddenly I felt YES. I will never forget that moment,” he says. “I knew nothing about discernment. But from that moment, I said yes.” In those days, it was commonplace for a hundred boys to enter the novitiate. “When I was a first novice we must have been about 70 of us. Now, what did that mean in terms of spiritual direction? Zero! The novice master didn’t have time to talk with us individually. I can only remember three times when I spoke to him individually,” laughs Fr O’Gorman. “That’s why I’m still here!”

The New York Province of the Society of Jesus shares a long history with the Philippines, which was a mission of the province until the late fifties. “I thought to myself, maybe I want to volunteer to go to the Philippines. There I was–a first year novice–and I went to the novice master and asked. He shook his head and said, ‘Brother they only send the best men.’ Meaning you’re not one of them! So I said to myself, I’ll show him!” By 1954, he was sent to study Philosophy at Berchmans College in Cebu. “So there I was, no real preparation or orientation for the Philippines, but beginning to build up friendships and get some sense,” he remembers. He was led to spiritual theology: “I was supposed to consider trying to develop things so that I could get into this business of spirituality. It was a very good thing, because already I had some sense of direction.” His three-year regency was in San Jose Minor Seminary, then located along Highway 54. “My job was to be the Prefect of Discipline and to teach English, Social Studies, Latin, World History. We really worked and had a really good community.”

He was sent back to the US for Theology. “That’s when I first experienced not really feeling at home in the US. Things in the US had been changing. Once again, I was very lucky because at Woodstock College we had fantastic professors–in scripture, theology, moral theology, even canon law–people who were already in what would become Vatican II. This was 1960.” By 1963, Fr O’Gorman was ordained to the priesthood in New York. “Interestingly, I should have been ordained by the Cardinal Archbishop of New York, Cardinal Spellman. But John XXIII, who had called for the Vatican Council, died. So Cardinal Spellman had to go to Rome. On the day that I was ordained [to the diaconate], there was no pope! However, the next day, I was ordained a priest–the same day that Paul VI was elected pope. Absolutely incredible! So when I had my first Mass, I could pray for Pope Paul VI.”

After his June ordination, he was sent to do pastoral ministry on Sundays. In November 1963, the American President John F Kennedy was assassinated. “So I went to the Jesuit parish, and the whites were in the front, the blacks were in the back. The blacks could not come to receive communion until after the whites. One of the announcements I had to make was that out of deference to the assassination of the President, the parish picnic for the blacks would be postponed. In other words, the parish picnic for the whites had already taken place.” It was a sign of the times: in a Jesuit parish, there was segregation.

By 1964, Fr O’Gorman earned his Licentiate in Sacred Theology. “I passed my exams–not because I was a superstar, I was a B student, but I passed–and I went to Rome and I learned Italian. It was a marvellous experience for me. I could have stayed in Rome forever! Not really, but a very good experience,” he says. “The (Vatican) council was still on, and we were beginning to see some of the changes–changes that before I thought were impossible. The need to be open to change is not always easy. You think everything is set.” In Rome, he had good professors and time to enjoy life. “I had to do a dissertation; I focused on Jesuit stuff. I had to read the letters of St Ignatius, historical documents, so I became very much aware of Jesuit things,” says Fr O’Gorman. When asked if he enjoyed it, he says “Yes. The thing is, because of the studies that I did, I was able to use them.” He received a doctorate in sacred theology from the Pontifical Gregorian University, and then came back to the Philippines.

By 1968 many things had changed. “In 1960, the automobiles were Ford, Chevrolet, American cars. Things were still very American. Filipinos were still the ‘little brown brothers’. Now it was all Japanese cars and ‘get rid of these colonial masters’. So the little bit of Filipinisation that I had experienced as a regent now really was full blown,” he recalls. “I was teaching at the Ateneo (de Manila University), really enjoying. I remember going along the corridor, and seeing on a board the names of certain American Jesuits, these men who had to go.” Fr O’Gorman remembers the moment clearly: “I wondered if my name would be there someday. While I was thinking about that, an ex-Jesuit novice who was a member of the student council came by. I said, when I see this list I wonder if my name will be there someday. And he says, yes, because last night at the student council meeting, we decided all American Jesuits have to go. He had just said it when the president of the student council came by. I said [to him], I understand that you decided that all American Jesuits have to go. He said, oh, not people like you, Father. But last night the student council had decided. He finally says, Yes, Father. So he confirmed that someday I would have to go,” shares Fr O’Gorman. “The movement was so strong, like now, Black Lives Matter. It was a strong wave. And of course, there was a lot of support for them.”

Faced with the reality of political turmoil in the Philippines, Fr O’Gorman says: “That put me into a situation where I had to think: should I stay or should I not? To be teaching pre-seminarians and be told, you cannot understand us because you’re an American.” Then the provincial offered him a sabbatical. “I went to the US to join the programme called the Institute of Religious Formation. Very good programme because it was partly psychological, so many good things that I had not really been trained in before.” For him it was very helpful for going on to spiritual theology. “Part of the programme was a 30-day retreat in Spain. So now I could really make the Spiritual Exercises! And it was a discernment, should I come back? I said, yes, I will come back.”

By then, the Philippines was under Martial Law. “[It was] another dimension of what it means to live in this world and be a minister of the church. I wasn’t discouraged,” he says. He lived in a good community and worked at Sacred Heart Novitiate: “Because I had experienced this whole business of renewal in the church, a lot of my work was trying to help other people experience and understand what this renewal means. I was organising seminars for Jesuits, and many of them were not just Philippine Province, but already working for the international–what we now call–the assistancy.”

The following years were fruitful. “Because of the work that I was doing here in the Philippines, I was getting to know people from other countries. Not yet Vietnam because it was still kind of closed, but Indonesia, Hong Kong. One of those years, I was asked to go to Japan to look at the theology formation of scholastics in Japan, to see what it was like and if it would be helpful for us in the Philippines,” he recalls. “I heard that there was a young professor there, very smart, named Nicolás. So I said, I will have to meet this Fr Nicolás. He didn’t live in the scholasticate, he lived in this small community: himself, a Spanish brother who was working in a shoe factory, and a Jesuit who was involved very much in social activism. I stayed in that community with Nicolás for a few days… never knowing that he would become the General, that we would become good friends.” (In 2017, Fr Nicolás would spend his last mission in the Philippines, part of the AIR community with Fr O’Gorman.)

He recalls a moment of grace in 1981 with Fr Arrupe. “Here I am in the Philippines, organising this programme for Jesuit renewal. Arrupe comes to visit Manila and I ask him if he’s willing to talk to this group. He says yes. So I had the privilege of introducing Arrupe to this group of Jesuits at the renewal programme. He gave a talk, then after his visit to Manila, he went to Bangkok. I saw him shortly before he was incapacitated.”

“I look back at these things I am so grateful for, over these many years,” he says. “We had very good history professors. And getting to know some of them personally, like, John O’Malley, we became very good friends. These were people I could invite to come to the Philippines to come to the renewal programmes.” He continues: “I really appreciate the value of history. And then we had very good moral theology, which is helpful for any kind of pastoral ministry.”

Fr O’Gorman’s missionary work was not limited to the Philippines. “Living here at Arrupe, I got to know some of the Myanmar scholastics. So one day Nicolás (then JCEAO President) comes into the dining room, sits down and says to me, the Archbishop of Yangon wants a Jesuit to give a retreat to his priests. Would you be available? I said, let me check my schedule!” During this trip to Yangon, he saw the other things the Jesuits were doing. “I came back to Manila, went to Nicolás and said, if you think I could be useful in Myanmar, I’m willing to go.” He lived with the candidates–who became scholastics sent to Arrupe International Residence later on. “I was giving retreats, getting to know the Archbishop who became the Cardinal (Cardinal Bo), and it really made me fall in love with Myanmar.” After two years, he came back to the Philippines and was missioned to Mary the Queen (MTQ) Parish. He calls them fantastic years, dealing with the people of the parish. “We had a good staff, Cesar Marin was the parish priest. The parish belonged to the same community as Xavier School, so we had our meals with them.”

And then one day he got a call from the Philippine Provincial, Fr Jojo Magadia SJ. “He said, I have a question for you: how would you feel if you were assigned to Arrupe International Residence? I said, my feelings are mixed! I don’t want to leave MTQ Parish! But I had been here twice before for different reasons, so I knew I could be happy at Arrupe International Residence.”

Fr O’Gorman says that a number of things that happened in his life were by chance.

“Believe it or not, although I can be very naughty, my main focus of my study in Rome was obedience. But a critical obedience!” he says. “Here’s a little example of crazy Jesuit obedience. St Ignatius says that there are three levels of obedience. Perfect obedience is you do what you’re told to do, you really want to do it, and you really believe it is the best thing. That’s the highest. Obedience of execution, will, and judgment. Then, not the highest form of obedience–you do what you’re told to do, you’re willing to do it, but you really think it’s not the best thing to do. That’s obedience of execution and will, but not of judgment. The lowest form of obedience is you do what you’re told to do, you don’t really want to do it, and you don’t think it’s the right thing to do. But it is still obedience!” he says with a laugh and a twinkle in his eye.