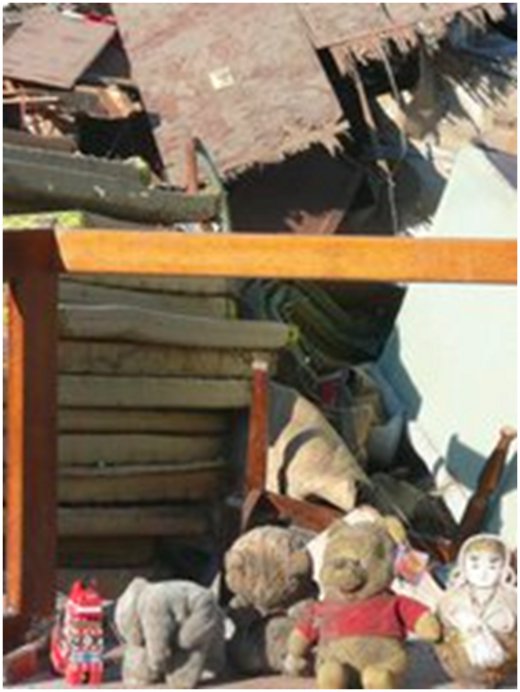

Jody Magtoto SJ was in Japan in May, helping in the relief effort for victims of the tsunami. He reflects on how he rediscovered his Jesuit identity in the midst of the rubble.

I had been in Kamaishi for two days by then. Because I had taken some courses in Japanese, I could sort of understand what was going on. But I came to realize that because my words and thoughts were in English, I could not articulate what I wanted to say. I decided then to keep my words to a minimum lest I offend or be misunderstood.

“Jody-san,” the quiet was broken by one of the volunteers. We had worked together that morning clearing up the debris from one of the houses. He sat beside me, and like me, looked towards the horizon. “I’m not a Christian, so forgive me for asking—what exactly does a Shingakusei do?”

“Well …” I began as I grasped for words, trying to explain in the simplest terms what being a seminarian is all about. He listened intently as I grappled to explain without theological jargon, in a mixture of Japanese and English, what theology is.

“So how many years does it take before Shingakusei becomes a shinpu?” he asked.

I explained the number of years it takes to become a priest, and as briefly as I could, explained the formation in the Society of Jesus. When he found out that I had been a software engineer prior to joining the Jesuits, he paused for a long time, then looked at me and asked, “But why? I mean, why leave all of that? That sounds like a well-paying and stable job.”

I was at a loss for words. How does one talk about vocation to a non-Christian?

I remembered the days when I was discerning whether or not to enter the Society of Jesus. One of the things that drew me towards the Jesuit way of life is the possibility of living a ministerial priesthood and at the same time specialising in more secular fields such as information technology. If I wanted to draw people to God, my very presence, as a religious and eventually a priest, would hopefully make people ask questions about God. And now it was precisely this question that I was faced with on a briskly cold Tohoku evening.

Rubbing my hands, and warming them with my breath, I again looked at the stars. “I suppose it is the same reason why you are here. You don’t have to be here. You could very well be doing something else.”

I continued, “You probably felt drawn to volunteer. I felt I was drawn to become a shimpu, a Catholic priest. It is quite difficult to explain, but I felt someone, I feel God is calling me. And ever since I responded to his call, I’ve never been happier. This call has brought me to do many things that I never expected to do — to visit unfamiliar islands, to teach religion in schools — tasks I wasn’t trained to do. Now brought me here to Japan, here at Kamaishi.”

My eyes fixed on the horizon again as my Jesuit life flashed in my mind – the joys and pains, the countless people who have helped me throughout this vocation. I don’t know for sure if what I said made any sense, but what I do know is that God was there with me at that moment. The God who has never left my side.