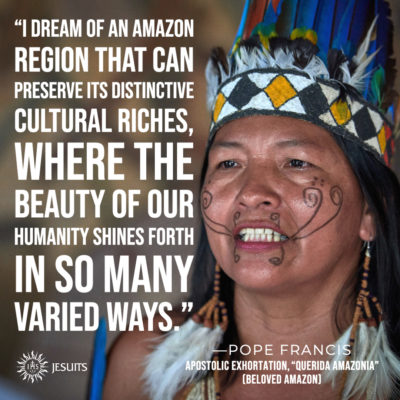

I am overjoyed with what I call the Indigenous Hermeneutics and Mystique (IHM) lens in the pages of the post-synodal exhortation, Querida Amazonia (QA) or Beloved Amazon. The sheer joy of reading the pages led me to exclaim: “Aha, this time, Pope Francis really got it!”

IHM enables him to hear the cries of the Amazonia: “Many are the trees where torture dwelt, and vast are the forests purchased with a thousand deaths … The timber merchants have members of parliament, while our Amazonia has no one to defend her … They exiled the parrots and the monkeys … the chestnut harvests will never be the same.”

Yet contemplatio offers a mystique for us to love and feel intimately a part of the Amazonia, like a mother to us (QA 55) as “the morning star draws near, the wings of the hummingbirds flutter; my heart pounds louder than the cascade: with your lips I will water the land as the breeze softly blows among us” (QA 20) and “enter[ing] into communion with the forest, our voices will easily blend with its own and become a prayer: ‘As we rest in the shade of an ancient eucalyptus, our prayer for light joins in the song of the eternal foliage.’” (QA 56)

This indigenous mystique is mystagogical as it is pneumatological. It is mystagogical as it is an ecclesial pathway of discerning with the bifocal “contemplatio from above” [a Trinitarian gaze on] and “contemplatio from within” the Amazonian Basin, with indigenous eyes and hearts.” (QA 55). This mystique thus offers the ecclesial governance a pneumatic mystagogy that gives primacy to the Holy Spirit (Ruach Elohim), noted for her outpouring of rich charisms (QA 89) on the world and the Amazonia in this challenging times. This ecclesial pneumatic mystique that focuses on Ruach Elohim (Spirit of God) articulates with the indigenous pneumatic mystique of the spirit world of the Creator, the ancestors, and nature, albeit not acknowledged in this exhortation and yet to be given theological importance in Christianity.

For indigenous wo/men healers, mystic, sages, and shamans, the spirit world is the “sacred power” of indigenous ancestral wisdom (QA 51), the “various beings” (QA 42) of indigenous mysticism (QA 73) that make possible buen vivir (good living, QA 8, 26, 71). This harmonious lifestyle of “less is more” (Laudato si’ 222) is premised on “personal, familial, communal, and cosmic harmony and finds expression in a communitarian approach to existence, the ability to find joy and fulfillment in an austere and simple life, and a responsible care for nature that preserves resources for future generations”. Indigenous peoples give a sense of joyful sobriety; they “enjoy God’s little gifts without accumulating great possessions; they do not destroy things needlessly; they care for ecosystems and they recognise that the earth, while serving as a generous source of support for their life, also has a maternal dimension that evokes respect and tender love” and “they have much to teach us” (QA 71).

In this epochal time of the Universal Church expressing her solidarity with the indigenous communities, including the “the good functioning of ecosystems [which] also requires fungi, algae, worms, insects, reptiles, and an innumerable variety of microorganisms,” (QA 49), can this pneumatic mystagogy enable the emerging Amazonian Church to recognise these discernible characteristics as manifesting the Ruach Elohim of buen vivir whose Divine Creativity-profundity is the Spirit power of the creator, ancestral, and nature spirits?

On the male imaging of the person of Jesus and the priesthood in QA 101, the prophetic moment to image women as imago Dei has been kairologically missed. Women and men are neither the face of Mary nor Jesus alone, but “both” and, more so, women, as imago Dei, are the face of Jesus/God/Spirit called to imitatio Christi and alter Christus, too. Noteworthy are the anguished cries of the Catholic Women Council (13 February 2020): “The theology behind this phrase is dangerous because it serves to exclude women from access to the full means of salvation. For there is an important ontological difference between Jesus and Mary – even though they are both human, Jesus is also God. The basis of the Christian faith is the conviction that Christ adopted human nature inclusively, not male nature exclusively, and thanks to this, every human being can be saved and is indeed divinized in Christ.” Should not the “ontological differences (i.e. equal but)… non-reciprocal relations” between female and male, “a sexual hierarchy… systematised as the structural sin of gender-based discrimination and violence against women in the home, in church, at the workplace, on the streets” (Sharon Bong 2019, 72) be dismantled/deconstructed? In engaging in this ecclesio-pneumato-mystagogy, is this not a discernible movement of the Holy Spirit within Christianity as the Ruach of imago Dei, imitatio Christi, and alter Christus?

In the context of the Amazonian women, it is discernible that God’s Ruach is alerting the local Churches to institutionalise a “laywomen ministeriality” related to the various and diverse priestly, prophetic, and kingly roles/ministries that should be given “stability, public recognition, and a commission from the bishop” so as to “allow women to have a real and effective impact on the organisation, the most important decisions and the direction of communities” (QA 103). Is it not opportune that this exercise of ecclesial pneumatic mystagogy motivate the emerging Amazonian Church to recognise this discernible sign of the movement of the Holy Spirit for the Amazonian women ministers to be given the rights to vote in synodal deliberations so that they have the noted real and effective impact on this emerging regional Church?

Is it not discernibly clear that the Amazonian Church needs to boldly appropriate indigenous beliefs and myths, religious festivals that have “sacred meaning and are occasions for gathering and fraternity” (QA 78) … ?

Last of all, I believe the “third way” (Austen Ivereigh January 12, 2020) resonates with the ecclesio-pneumato-mystagogy of Pope Francis that discerns how the Spirit blows and opens up the Amazonian Church “to new thinking in order to implement the vision of Laudato si’, lifting his encyclical off the page and putting it into action” as integral to the evangelising mission of the Amazonian Church through “a renewed inculturation of the Gospel in the Amazon region” that puts on “a distinctive kind of holiness, that will in turn act as sign to the whole Church” that “the Gospel/Spirit will triumph over technocracy”. Is it not discernibly clear that the Amazonian Church needs to boldly appropriate indigenous beliefs and myths, religious festivals that have “sacred meaning and are occasions for gathering and fraternity” (QA 78), to creatively inculturate in the liturgy “the many elements proper to the experience of indigenous peoples in their contact with nature, and [to] respect native forms of expression in song, dance, rituals, gestures, and symbols” (QA 82)? The reason is that these are all “charged with spiritual meaning” and “can be used to advantage and not always considered a pagan error” (QA 79 cf. 78).

At the same time, is the Holy Spirit that blows where she will not prod the Amazonian Church towards these beliefs, myths, religious festivals pneumatically “bursting forth” in the Creator-ancestral spirits that vicariously defend the inalienable legacy of Peoples Living in Voluntary Isolation (PIAV/PIACI) and vehemently resist a predatory and colonialistic-capitalistic God who legitimises “crimes and injustices” (QA 14), which systematically decimate their religiocultural heritage, their sacred wisdom, their ancestral homeland, and shared biome with missionary agents who ride roughshod over their women, men, youth, and children, with their lethal power of the gospel, goons, guns, and germs?

The vision of an Amazonian polyhedronic Church (QA 29-32), with its own distinctive indigenous holiness (QA 77), lay ministeriality, ordained permanent deacons/nesses, and priests who are reputable married community leaders (QA 85), will be left to the exercise of a pastoral discernment on “a higher plane” that transcends lamentable polarities (QA 104; Evangelii Gaudium 228). The exhortation in QA 89 is the most emboldening pathway for this ecclesial pneumatic mystagogy: “If we are truly convinced that this is the case, [referring to the shortage of priests for the Eucharists and reconciliation], then every effort should be made to ensure that the Amazonian peoples do not lack this food of new life and the sacrament of forgiveness.” As Cardinal Raymond Gracious of India averred in an exclusive interview in Rome on 25 October 2019, the Canon Law offers such provisions for the local Churches to discern and deliberate. This exhortation looks favorably on the ongoing synodal deliberation of the emerging structure of the Amazonian Bishops’ Conference and the content of the Amazonian Rite, with its context-specific presbyterial-ministerial expressions. The papal approval is there when the documents are ready.

Fr Jojo M Fung SJ from Malaysia-Singapore Region is a Visiting Fellow at the University of Oxford. He served as Coordinator of the Jesuit Companions in Indigenous Ministry of the Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacific for 20 years, from 1999 to 2019.

Fr Jojo M Fung SJ from Malaysia-Singapore Region is a Visiting Fellow at the University of Oxford. He served as Coordinator of the Jesuit Companions in Indigenous Ministry of the Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacific for 20 years, from 1999 to 2019.

Hermeneutics – a method of interpretation, especially of Biblical or literary texts

Mystagogy – a discerning process of the religious experience of the movement of God’s Spirit in our lives and our world

Pneumatology – the study of the Holy Spirit