In the last year, educators everywhere found themselves involved in an unforeseen global teaching experiment. As a result of the pandemic, teachers had to quickly learn how to pivot to online teaching.

In the last year, educators everywhere found themselves involved in an unforeseen global teaching experiment. As a result of the pandemic, teachers had to quickly learn how to pivot to online teaching.

Few of our teachers had been prepared for this shift, with little time to find ways to equip themselves with the skills to deliver their courses online. Understandably, many Ignatian educators were initially reluctant. Online learning was dismissed as inappropriate for Jesuit education, if not downright ineffective.

The fear at the time was that all the defining markers of Jesuit education would be compromised, if not totally sacrificed, in the online environment. Magis, for example, is an important element of our brand of education–that commitment of both students and teacher to excellence. But given this far-from-ideal situation of online learning, how can teachers possibly challenge their students to strive for excellence? We would be lucky if they even perform the tasks we assign to them.

Another hallmark of Jesuit education is cura personalis–or the personal care for every individual student. How can teachers provide this kind of care in an online lecture, where instead of the actual presence of students, we find ourselves facing a computer screen with the videos of most students–all too often–switched off?

And let’s not even talk about Ignatian Pedagogy, with its emphasis on Experience, Reflection, and Action. It’s tough enough to implement this pedagogy in our traditional face-to-face classes, how much more challenging would that be now that we’ve gone virtual?

The first Jesuit educators

The good news is that Jesuit education belongs to a larger tradition and a longer history, which can offer us some instructions on how to proceed in a time like this one.

Former Jesuit education secretary Fr Gabriel Codina had this to say about the early Jesuit schoolmasters: “Thus the first Jesuits went as it were to the supermarket of education.”

By “the supermarket of education,” he meant the programmes, practices, and strategies that were already available then and that they could “beg, steal, or borrow” from experts and leading educators of the day. Those early Jesuits understood that a truly good education “requires continuous renewal, innovation, reinterpretation and re-invention, and that if they wanted to actually provide quality education, they have to be attentive to the always-changing context and open to new developments”.

Now that’s a very timely reminder for us because Ignatian educators today are being challenged to resist remaining complacent about the way we have been going about our business of education.

AteneoBlueCloud

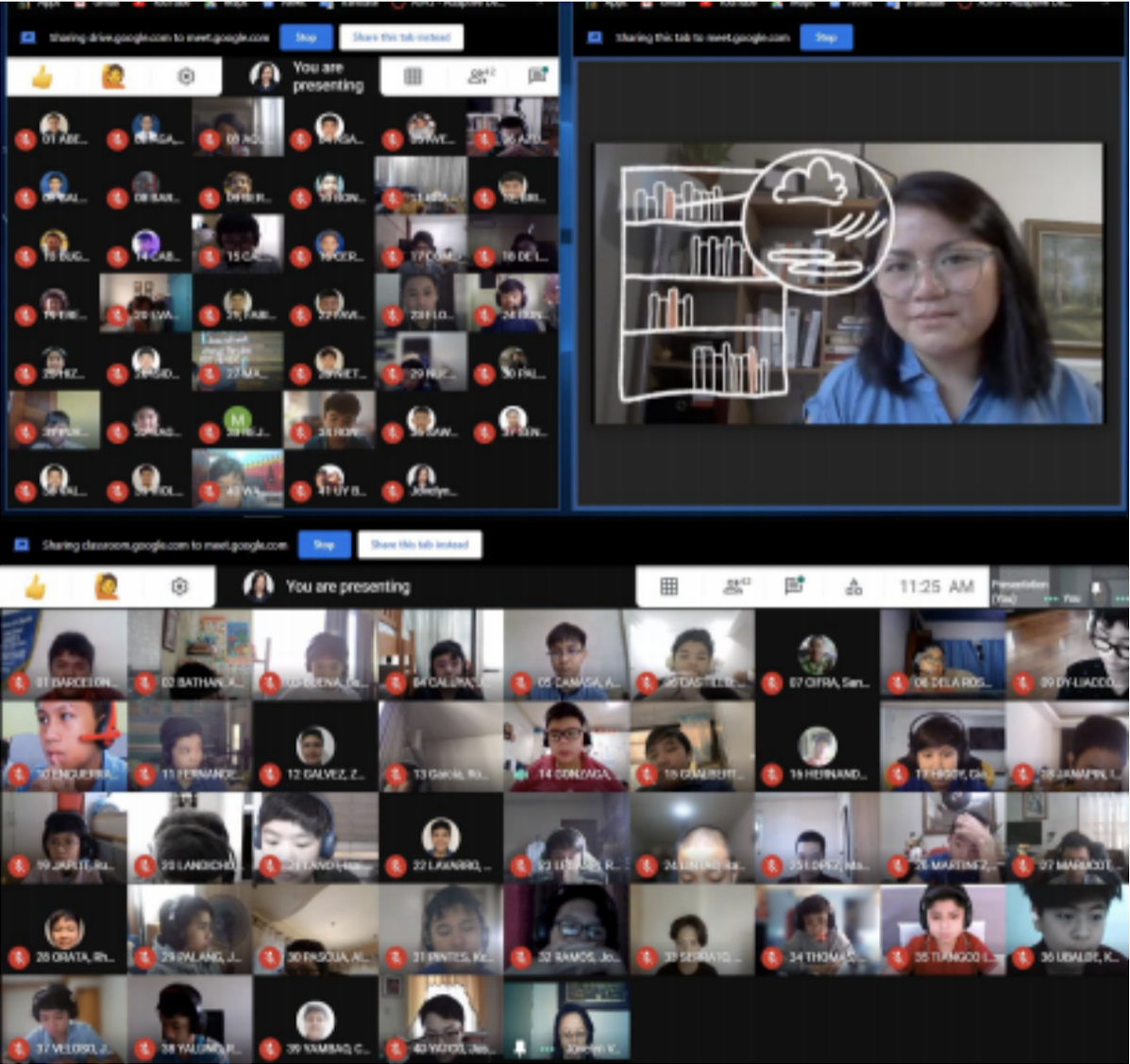

In the Ateneo de Manila University, when it was clear that all classes would be held online, we decided not to rush into things. We didn’t immediately jump into the bandwagon of scouting for the best learning management system or video conferencing platform. We restrained ourselves from attending every single webinar on online learning and teaching because a more fundamental question needed to be answered: How should online Jesuit education look and sound like so it would truly be “Jesuit”?

We needed to define the elements of an Ateneo– and Jesuit–education that we should make sure to preserve and even strengthen when we go online. How do we brand our online education so that the online education we offer our students would be truly “Jesuit”?

The AteneoBlueCloud was the strategy we came up with to offer not only engaging and effective learning experiences for our students, but also to strengthen the defining ingredients of a Jesuit education. We consulted our stakeholders, especially our faculty and even some of our students: “What do we consider most essential for us in our face-to-face education that we want to preserve and strengthen in the AteneoBlueCloud as we go online?”

Two principles stood out from the conversations. The first principle may seem obvious, but it is so fundamental that we felt it needed to be spelled out explicitly: Technology is but a means to learning and formation. It’s not about being as technically sophisticated as possible–not at all about having at our disposal all the latest software and hardware. Rather, it is unequivocally about our goal of learning and formation for our students.

The second thing we agreed on is that it’s not so much about the mode of delivery. For example: Are we going to be more synchronous or more asynchronous? Rather it’s about the design. And here is where Ignatian Pedagogy comes in.

In designing virtual experiences, we asked ourselves the following questions:

In designing virtual experiences, we asked ourselves the following questions:

What is the array of possible online learning experiences we can offer our students so they will be engaged and learn?

What are students’ experiences like during a typical Zoom class? Will the teachers simply flash their slides and deliver the usual lectures as if the class was physically present? Or will they chunk their lectures into bite-sizes and use the Chat Box occasionally to solicit feedback from their learners or check their understanding? Will they take advantage of the polling function so that the class becomes more interactive? Will they assign students to breakout rooms so that learning doesn’t remain an isolated experience and students actually get to interact with their classmates?

How do we encourage our students to engage in Reflection, even if our discussions are virtual, whether during live Zoom sessions, asynchronous Discussion Boards, or blogs?

Online learning offers a valuable opportunity for our students to become more independent and critical thinkers. In the online environment, they have the opportunity not to be too dependent on their teachers and to learn to think and process things on their own. The Ignatian term for that is Reflection.

If we examine the culture in social media and the internet, there prevails an anti-reflection online culture. The culture that results from the internet does not encourage reflection at all. As a result, Reflection has become an endangered practice.

Nicholas Carr, in his book The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brain, talks about the reverse evolution that’s happening to our mind.

The evolution of human civilisation shows a shift from human beings being hunters and gatherers of food to becoming cultivators of food. With the advent of agriculture, humans began to settle down, cultivate their own food, and form more permanent societies.

Carr’s observation is that there is a reverse evolution that’s happening today–not in food production, but in knowledge production, not in agriculture, but in information. Because of easy access to online information and the resulting copy-and-paste culture today, all of us who are users of technology tend to stop being cultivators of personal knowledge.

Isn’t that what Reflection is about? When we mull over information and process it, we are reflecting on it and we are cultivating, nourishing, and growing our own personal knowledge. This cultivation takes time, takes patience, but unfortunately, that’s no longer in fashion today.

What’s happening today is that more and more young people–as well as adults–are becoming mere hunters and gatherers of information in the digital forest. We just want to pick all this information that’s out there and not spend enough time and attention to cultivating our own personal knowledge, which is the result of reflection.

So by default, reflection is not encouraged today, but this shift to online learning can make us more deliberate and more mindful of the need for Reflection.

Finally, how can we promote Action online so we can make sure our students will actually use and apply what they have learned “in the real world”?

Jesuit education is about forming persons for others so that when our students graduate, they will aim to serve the world, keeping the common good before their eyes and making a difference.

We had to study designing effective formation programmes for an online environment. To our pleasant surprise, the internet stretched the horizon of possibilities for our students. We experimented with distance Service Learning and vicarious immersion programmes, which– while admittedly not ideal–turned out occasionally to be powerful and transformative experiences for our students.

For reasons we had not foreseen, the online sharing turned out to be more inclusive and more personal: Because they had more time to prepare what to say, even the introverts got to share, and perhaps because of the genre of online writing, the quality of sharing seemed deeper and more personal.

Ignatian educators all around the world are still experimenting and learning from their teaching experiments. But two things already seem evident. First, contrary to our initial apprehensions, with proper design, the defining elements of Jesuit education can, in fact, be promoted and even strengthened. Second–again to our surprise–the online mode of learning actually stretches the horizon of possibilities for designing the students’ Experience, Reflection, and Action.

Johnny Go SJ

JCAP Secretary for Secondary and Pre-secondary Schools

Director, Ateneo de Manila Institute for the Science and Art of Learning and Teaching

This article was first published in “The Jesuits in Asia Pacific 2021”. To download the report click here.

For a related talk from the author of the same title, delivered at the Jesuit Education Forum conducted by the Wah Yan Colleges, click here.