August is a symbolic month dedicated to peace movements in Japan. Seventy-one years have passed since the defeat of Japan in the Second World War, but the dropping of the first two nuclear bombs on Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (August 9, 1945) are still vividly remembered.

August is a symbolic month dedicated to peace movements in Japan. Seventy-one years have passed since the defeat of Japan in the Second World War, but the dropping of the first two nuclear bombs on Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (August 9, 1945) are still vividly remembered.

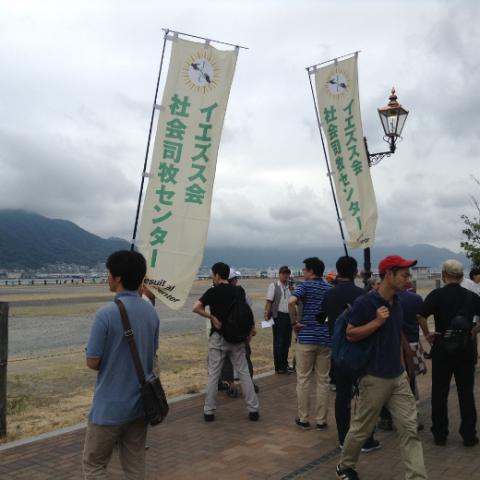

A group of 34 Jesuits, half of them from Korea and the rest from Japan gathered in Shimonoseki, in the west of Japan from August 23 to 26 to heal wounds occasioned by the worst historical relationship between both countries and to search for closer cooperation.

The four-day workshop was intense with inputs on the historical realities of Koreans in Shimonoseki, the much-protested new Henoko American military base in Okinawa, and pastoral care of migrant workers on Kyushu Island.

A full day was dedicated to fieldwork in Shimonoseki, the gate port of Japan after it annexed Korea in 1910. The participants visited various sites that commemorate the landing of forced Korean workers into Japan before and during World War II and heard about the life of one such worker.

A full day was dedicated to fieldwork in Shimonoseki, the gate port of Japan after it annexed Korea in 1910. The participants visited various sites that commemorate the landing of forced Korean workers into Japan before and during World War II and heard about the life of one such worker.

They met a man Fr Ando Isamu SJ, a staff member of the Jesuit Social Centre in Tokyo, Japan, calls “a living historical symbol of former Korean workers”. To maintain his privacy, we call him Mr Kim.

The group met Mr Kim at a school for Korean students. He is 95 years old but spoke with clarity about his life experiences in Japan. “I was young and spoke a little Japanese. I was attracted to leave my village to find a job in Japan,” he told them smilingly in both Japanese and Hangul. In 1942, at the age of 22, he boarded a Japanese ship that transported thousands of Korean workers from Pusan to Shimonoseki, a mere five-hour journey.

“We were over 300 workers, packed in the bottom of the ship. They gave us the same shirts with a different number on the back and from that time, they only called us by that number.

“As soon as we arrived at the piers of Shimonoseki, they put us in crowded warehouses where we waited for the trains to come. Inside the freight train we were blindfolded; we did not know where we were headed. I arrived at Tochigi Prefecture without knowing the place and job I was supposed to do. All I had was a ‘furoshiki’ with my belongings. Together with my companions I was assigned to work in a dam to dig a hole for water pipes. They placed us in a packed bunkhouse. The work was very hard from early morning ‘till late evening. We were only given a rice ball at night. The sanitary conditions were very bad and although there was a river nearby, the water was frozen so we couldn’t bathe.

“As soon as we arrived at the piers of Shimonoseki, they put us in crowded warehouses where we waited for the trains to come. Inside the freight train we were blindfolded; we did not know where we were headed. I arrived at Tochigi Prefecture without knowing the place and job I was supposed to do. All I had was a ‘furoshiki’ with my belongings. Together with my companions I was assigned to work in a dam to dig a hole for water pipes. They placed us in a packed bunkhouse. The work was very hard from early morning ‘till late evening. We were only given a rice ball at night. The sanitary conditions were very bad and although there was a river nearby, the water was frozen so we couldn’t bathe.

“Every day we were indoctrinated to work for ‘the country’. So I did it and was considered a model worker. One morning, while leaving for work, we saw a fellow countryman who had tried to escape hung upside down and whipped in front of our eyes. One Sunday, I got permission to go out with another worker of good standing. Together, we went to a hot spring and made our escape from there. I ended up in Kobe. My knowledge of the Japanese language offered me opportunities to work as a teacher and remain unknown in Japanese towns.”

Although he looked tired, Mr Kim’s smiling face did not show any hate for his Japanese oppressors. He is one of more than 600,000 Koreans living in Japan, many of whom were workers brought forcefully to Japan, or like Mr Kim came looking for a job and had to remain in the country.

Hearing these realities first hand has inspired the Jesuits from Korea and Japan to work closely within the framework of the migrants’ network of the Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacific.

Main photo: A monument remembering Korean workers brought to Shimonoseki who died during World War II