Introducing the Universal Apostolic Preferences

The Universal Apostolic Preferences:

Vision, Faith, and Renewal

What are they?

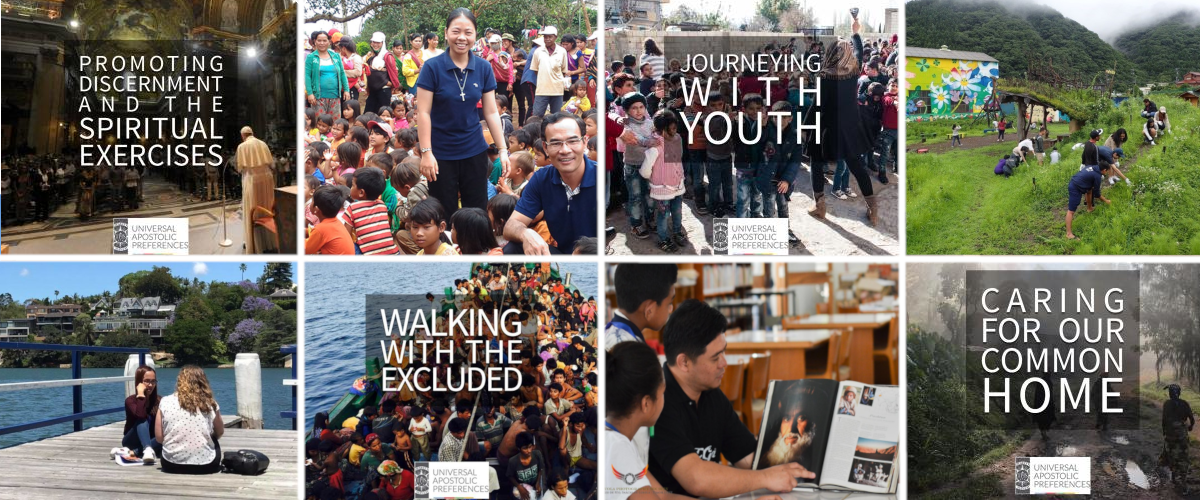

At the very simplest level, we are talking about four aspirations, four statements of intent and purpose:

- To show the way to God through the Spiritual Exercises and discernment;

- To walk with the poor, the outcasts of the world, those whose dignity has been violated, in a mission of reconciliation and justice;

- To accompany young people in the creation of a hope-filled future;

- To collaborate in the care of our Common Home.

Even in official sources, the formulations, and also their order, differ a bit. But it’s important to see them not as simple nouns (spirituality, ecology), but rather as phrases denoting action, phrases centred on verbs. In his letter promulgating the preferences, Fr Sosa presented them as the culmination of an attempt ‘to find the best way to collaborate in the Lord’s mission, the best way to serve the Church at this time, the best contribution we can make with what we are and have, seeking to do what is for the greater divine service and the more universal good.’[2] They set out a programme for the next ten years.

And we can let Fr Sosa speak for himself by looking at a video made in his office.

How did they come about?

The discernment process

There’s a simple and short-term answer to this question. We can begin in the summer of 2017, just after Fr Sosa had come into office. GC 36 had asked him to review progress on the previously existing universal apostolic preferences, and if appropriate to renew them.

In the autumn of 2017, Fr Sosa wrote to us all, inviting us to engage in a process of discernment in common in which Jesuits and apostolic partners should all take part. The results gradually filtered upwards, until there was a final week-long meeting of his extended council – about 25 people — last January. My sense is that on the ground the discernment process was pretty patchy – but as the matter proceeded up the authority chain, the process improved significantly, and the people concerned became successively more euphoric, and indeed consoled.

The results were then submitted to Pope Francis, and received back from him as a mission. The preferences are not simply ours – we have been following the Spirit and they have been confirmed by the Pope. That may sound a bit artificial, if not indeed jesuitical. One wonders if we would have tried this with another sort of Pope. But the procedure was eminently traditional. It echoed the process by which Pope Paul III in 1540, and subsequently Julius II in 1550, approved the initial founding of the Society. Then too, there were processes of deliberation and discernment among all the companions, leading to the submission of a document to the Pope. Then too, the document was subsequently given back to the Society on the Pope’s own authority. Then too, discernment in common preceded and informed (in the full sense of the word) the giving and receiving of a mission.

The Previous Preferences

During, or perhaps even before, this process, the meaning of the term ‘universal preference’ changed. We have ended up with preferences that are meant to inspire all of us on a daily basis. They are offering every Jesuit and everyone associated with the Jesuit mission a vision to keep in mind constantly – to echo the Formula of the Institute. Or, to use the phrase falsely attributed to Pedro Arrupe, they give us all a reason to get out of bed in the morning.

When Fr Kolvenbach formulated his Universal Apostolic Preferences in 2003, the purpose was effectively different. What were the universal needs that might be neglected in regional and provincial planning? Fr Kolvenbach came up with five answers to that question: Africa, China, the intellectual apostolate, the Roman Houses, refugees. Not many of us, I suspect, could have rattled off Fr Kolvenbach’s list more than fifteen years on without a prompt. His version of Universal Apostolic Preferences focused precisely not on what would motivate all of us every day, but rather on what wouldn’t – what wouldn’t that was nevertheless important and that required special attention and effort. The question motivating Fr Kolvenbach’s project remains important, even perhaps urgent. We need both kind of universal preference. As a member of staff in a formation centre, I sense that government by local provincial is for some of our purposes quite dysfunctional. As Fr Sosa’s letter of 19 February half acknowledges, these new preferences may have grown out of what Fr Kolvenbach sought to do, but they do not really supersede his results.

Aggiornamento and renovatio accommodata

But both Fr Sosa’s and Fr Kolvenbach’s processes need to be seen in a longer and broader context. As we all know, human culture in the twentieth century underwent profound change, and Christianity with it. Vatican II was a moment of recognition that we needed to take stock of ourselves and do things differently, rethinking our way of life from first principles. Like all religious orders, we undertook a process of sensitive renewal (renovatio accommodata), simultaneously responding to contemporary needs, to ‘the signs of the times’, and retrieving our original, foundational purpose and charism (Perfectae caritatis, n.2) The task was large. It has occupied us for two generations. It is indeed a continuous task, one which we must be taking up again and again.

It is not surprising, then, that every General Congregation since Vatican II has in various ways felt the need to find a new expression of what the Society is about: in 1965 the resistance against atheism; in 1975 the struggle for faith and the promotion of justice; in 1995 the interplay of faith, work for justice, interreligious dialogue and engagement with culture; in 2008 and 2016 the ministry of reconciliation. The documents expressing these visions suffered because they were written in a couple of months by an international assembly of more than 200 people, with an above average distribution of strong-willed and opinionated characters.

Fr Sosa has tried a different process, and come up with a different result. Instead of a committee document produced quite quickly, here we have had a process of discernment lasting a longer time. Instead of a treatise on pastoral (or practical) theology, we have received simply four one-phrase aspirations, supported by a commentary, designed to guide our actions for about 10 years. What has emerged is, in my opinion, simpler, more coherent, and better written than anything a General Congregation could produce. What is it to engage in the Jesuit mission today? To seek God’s will, to promote discernment, to walk with the poor, to accompany the young, to collaborate in caring for the earth, our common home.

What does Fr General wants us to do with them?

Openings to Grace

Here I have a little inside information. It so happens that I’ve been at two different meetings in Rome this month, one of which was addressed by Fr General himself and the other by John Dardis, his assistant for discernment and apostolic planning. Both made it very clear – more so even than in the letter Fr Sosa has just sent us this Easter Sunday — that that these Universal Apostolic Preferences were not simply a list of requirements for us all to meet. It is not enough for a province to create a Laudato Si’ community, to open – as the Francophone province has done – a new centre for young adult ministry, or to take various initiatives to reinforce social ministry. Those things are legitimate, even important – but secondary. Something more important was at stake.

These new Universal Apostolic Preferences need to be seen as openings to grace. Yes, we co-operate. But the real agent is God. The clip begins with an invitation. ‘Imagine God speaking to you.’ For all that planning is important, there is something greater than planning here. In his Easter Sunday letter Fr Sosa tells us that the preferences are ‘orientations, not priorities. A priority is something that is regarded as more important than others; a preference is an orientation, a signpost, a call.’ I am not sure that the contrast between nouns here communicates very well, especially across a language barrier. Reality is greater than ideas, or at least than nouns. So let us try a longer approach.

One of the auxiliary bishops in Paris is an old boy of our secondary school there. In the last two months, I’ve been at two major liturgies he has celebrated: one for the Society, one for a group of consecrated women. At both, he quoted from an elderly Jesuit at St Louis Gonazgue speaking at a celebration of his 60 years as a Jesuit. ‘When I joined, I thought I was making a great gift to God – gradually I have learned that it has been God who has been doing the giving.’.

That pious vignette takes us into the interplay between our action and God’s. My sense of Fr General’s concern about these preferences is that they should point us, in ways that transcend considerations of planning, to places where God’s word can be heard, God’s gift can be received, in particularly clear and challenging ways. Places of vulnerability, places that might seem threatening: the realities of the marginalized, and of abuse within the Church; of the young who think differently, who are digital natives and who perhaps evoke guilt in baby boomers about how they have been sold short; the challenges of climate change, and of counteracting ‘the environmental destruction being caused by the dominant economic system’. It’s about letting God change us.

In his February letter Fr Sosa stresses the idea of continuing conversion. For his part, Pope Francis, in ratifying the preferences, commented that the first preference, with its focus on God and spirituality, is primary – ‘without this prayerful outlook, the rest doesn’t work (sin esta actitud orante lo otro no funciona)’. True, of course. But we should not hijack this point, and use an unexceptionable piety about the primacy of God to deaden our spiritual senses. The other three preferences are themselves also in the strong sense theological (theologal). They point us to where the human race is growing, the places where our collective consolations and desolations seem to be concentrating. They are being identified as privileged natural means through which God will change us, leading us beyond ‘every form of self-centredness’. In short, the preferences are ‘orientations that go beyond “doing something”’. They should bring about transformation – personal, communal, and institutional. They are meant to stretch us.

Let me be a little personal. As a university teacher with pastoral commitments, I deal a lot with young people in their twenties as their mentor or teacher. More recently, I’ve had some limited experience working for a Jesuit project as part of a team including young people who were not born when I started teaching. I’ve found that challenging. They think differently; I may have a bit more experience of life, but they have an energy and freshness than I no longer have. It’s good for me. It jolts me forward. I can say something similar about my encounters with the encounter with the enormous reality of child abuse. For me this began a long time ago, very soon after I was ordained. I was assisting and supplying for a colourful English Jesuit, Algy Shearburn — not the most obvious mentor for someone like me – in a prison in the North of England. Algy encouraged me to pay special attention to the isolation unit – ‘try and visit them every day old man. I think our Lord would be very kind to the rule 43s’. I did, and I found myself confronted massively with people who had been both abusers and abused. It started a process within me that has, slowly and over time, focused me on my own vulnerability in ways that I could never have foreseen, and for which I am profoundly grateful. To repeat: these preferences are not just about what we do. They are also about how God can change us.

Atheism and Secularisation

The last time a pope gave us a mission of this general kind, it came simply from above – in those days we didn’t talk about communal discernment. In 1965, Paul VI addressed the 31st General Congregation that was about to elect Pedro Arrupe as General, and gave the members, by virtue of the special vow of obedience to the Pope for mission that many Jesuits take, the charge of counteracting ‘the atheism spreading today, openly or covertly, frequently masquerading as cultural, scientific or social progress’. He used confrontational, military language. Jesuits were to ‘fight the good fight, making all the necessary plans for a well-organized and successful campaign’. St Michael the Archangel, no less, was to be the guarantor of victory.

Paul VI was sometimes courageously creative, but here perhaps an assembly of Jesuits evoked his anxiety about the great changes that he did much to enable and encourage. If, like Pope Francis and Fr Sosa, you take your lead from a document such as Evangelii nuntiandi, something different emerges. Yes, we need to resist secularism in its older and its newer forms. But nevertheless ‘secular society’ is something positive – ‘a sign of the times that affords us the opportunity to renew our presence in the heart of human history’ (emphases original). We need to avoid the nostalgia for the expressions of religion proper to a past culture. ‘In a mature secular society, the conditions exist for the emergence of circumstances conducive to personal religious processes, independent of social or ethnic pressure, that allow people to ask profound questions and to choose freely to follow Jesus’. Secularization is not a problem, but rather a condition that enables a new level of Christian maturity. This vision is challenging. Perhaps we are not yet fully ready for it. But it has the potential to free us up.

Secularisation encourages us, forces us, to take our place ‘in the heart of human history’ – not as lieutenants of Michael the Archangel, as agents of a divine authority confronting cosmic sinfulness and retrieving souls from the disaster which is the creation. Confrontation and condemnation are absent from the language of the Universal Apostolic Preferences. The theme is rather of collaboration in an enterprise larger than ourselves, an enterprise that is of God, an enterprise in which we are but one of the agents. ‘The preferences are an opportunity for us to feel that we are the least Society in collaboration with others (mínima Compañía colaboradora).’

Beyond the Self-Referential

It’s worth looking at the language in which the preferences are couched (though some of the marketing has simplified this). ‘Show the way to’; ‘walk with’; ‘accompany’; ‘collaborate’. We are close to the vision of the Church that Jorge Bergoglio expressed in his speech to the cardinals before his election: a Church called to go beyond itself, to move beyond self-referentiality and theological narcissism. And as our theology of grace increases in scope and generosity, so our sense of our own uniqueness in the process may decrease.

Thus the first preference is not centrally about the Spiritual Exercises, but about showing the way to God. The Exercises and discernment come in only as means. We might compare how Ignatius himself, in the first and eighteenth Annotations, relativises his own programme. The second is not primarily about our service of the marginalized – it’s about a mission of reconciliation and justice rooted in an option to walk with the poor, the outcasts of the world, and those whose dignity has been violated. The third is not about our teaching of the young – it’s about accompanying their creation of the future. And whereas the first three can draw on our tradition, the fourth, about collaboration in care for our Common Home, cannot, because it depends on a quite new sense that our agency, our creativity, our entrepreneurship, our moral behaviour – all these need to be seen not just in relationship to God but also to the rest of creation. Finally, the prominent references to abuse give us a new freedom to see that the Church, for all that it remains central to all we do, can in practice be not only the sign of the solution but also a large part of the problem. Injustice lies within us as well as beyond us. Getting that point right has been too difficult for much Catholic theology.

What kind of faith and hope?

Hope and Collapsology

It remains the case, however, that, the Universal Apostolic Preferences seem informed by a startlingly bold optimism. The second preference emerges from a conviction that globalization can be something other than a process of market-driven homogenization. We can recognise ‘multiplicity of cultures as a human treasure’, protecting cultural diversity, and promoting ‘intercultural exchange’. The third makes no reference to the crisis of transmission in the faith to the next generation so familiar to us in the West. Instead, it evinces a confidence that the ‘anthropological transformation that is coming to be through the digital culture of our time’, and of which young people are the principal agents, can attain a good outcome. This ‘new form of human life … can find, in the experience of encounter with the Lord Jesus, light for the path toward justice, reconciliation, and peace’. Likewise, the fourth preference avoids catastrophism. In the promotional video, Fr Sosa presupposes that we can still act to stop the deterioration of our Common Home, and leave it in a good state for future generations. ‘It’s still time to change the course of history.’

It is, of course, theological hope in the promise of the resurrection that underlies such statements. But perhaps we need to bear in mind the paradoxical, paschal character of this hope. Just before I was coming away from Paris – the day after Notre Dame had nearly burnt down – I was at supper with one of the younger members of my community, and perhaps even, in my small way, accompanying him. He is someone I admire, and someone whose leads in matters ecological I find edifying. He seemed a bit sad. He had been reading in a trend in French thought called – bizarrely — collapsologie. Collapsologie brings together in a distinctive way a wide range of different disciplines. It draws connections, for example, between economic analysis, what we know from archaeology about the end of ancient civilizations, scientific analyses of climate change and the destruction of ecosystems. On that basis, its leaders argue forcefully that the breakdown of our civilization is far closer than we think. Collapsologists have not completely abandoned hope, but their forecasts are nevertheless catastrophic. Rather movingly, our conversation turned to the implications for Christians. ‘At the moment we’re like the disciples at the Last Supper. We’re eating and drinking away, and have no idea what’s coming.’

Easter Traditions

There are obvious reasons why Fr Sosa chose Easter Sunday to send us another letter on assimilating and implementing the new preferences. But when Ignatius presents us with the office of consoler that Christ our Lord bears, he does not simply say that all will be well. Rather, he invites us to make comparisons with how friends generally console each other (Exx 225). There are continuities, yes – but there is also something startlingly new, unique. Ignatius starts a process – a process that might take many different forms — rather than declaring a doctrine. Nouns – even positive ones like ‘hope’ and ‘resurrection’ – are too simple, too prone to ideological misuse. The truth here can only be learnt by doing, by a process of exploration that engages the hard facts. As the poet T. S, Eliot put in ‘The Dry Salvages’, apprehending the incarnation

… is an occupation for the saint—

No occupation either, but something given

And taken, in a lifetime’s death in love.

The preferences make sense only in a mysterious, paschal space.

How should we re-imagine ourselves?

Revisiting the Ignatian Refounding

Something big happened in the twentieth century that changed the way religion functioned. For the whole Church this was destabilising and challenging. But perhaps – though we must be careful here — for the Jesuit movement these changes enabled us to understand what our foundation was really about. It was only at this period that we began to talk about Ignatian spirituality and Ignatian mission, in ways that might well be deeply authentic, but that went far beyond the historical Ignatius. Whatever we make of that claim, the process has required work. We have been at it for fifty years, and we have by no means come to the end. Fr Sosa’s Universal Apostolic Preferences represent but one more step – they will not be the last.

My intuition is that we are being invited to look again at a big decision, a refounding decision, taken by Ignatius and his first companions within a few years of the Society’s foundation. The first companions had been marginal, indeed suspect, on the fringes both of the Church and of wider Society. But, for whatever reason, they grew enormously after 1540, particularly in Portugal and in Spain. And they faced a demand that the colleges they founded for the training of their own recruits be opened more widely. In saying yes to this demand, they modified radically, with Ignatius fully implicated, their commitments to poverty and mobility. They became respectable; for better or worse, they became important agents of authority in Western culture. They made this choice, perhaps not fully consciously, in the service of what they saw as a greater good.

It would be silly for us to criticize that change. We would not be here if the early Jesuits had not made it. But nor should we see it as something which binds us permanently. Perhaps we are being invited now to position ourselves to see that choice as a choice of its time, one that we can and should let go of. Perhaps we should be content no longer to run our own projects but rather to help others run theirs. In 1978 Karl Rahner wrote a piece he regarded as his ‘spiritual testament’, in which he imagined Ignatius speaking to a contemporary Jesuit. There, as is well known, he set not doctrinal instruction but the experience of God fostered by the Exercises at the heart of Jesuit mission, and in his way anticipated these new Universal Apostolic Preferences. But what are less well known are the musings of Rahner’s Ignatius about how his movement related to society at large. It may have been a historical necessity for the first generation of Jesuits to accept a secure place in élite circles, and to ally themselves with what historians now call the forces of social disciplining in early modern Europe. But does that have to be the case into the future? Didn’t that choice imply giving up things that had been central to the charism? It is perhaps significant that institutional education – for all the stress Fr Sosa and his predecessors have laid on intellectual depth – is not itself one of the preferences.

Revisiting the Formula

The new Universal Apostolic Preferences resemble in their purpose the first major paragraph of the Formula of the Institute. Both documents evoke the main things Jesuits should be trying to do, as purposes constantly to be kept in mind. Both, too, encourage us to go deeper: to keep God before our eyes, and the underlying point of the Institute, that of being a sort of pathway to Him (instituti rationem, quae via quaedam est ad illum). The Formula is obviously historically pivotal and uniquely authoritative. But a profound change of religious consciousness has nevertheless intervened, and things need to be different. In the Formula, every Jesuit “should propose to himself (proponat sibi)” that he is part of a Society that strives to defend and propagate the faith. The focus is on our actions. But in late modernity and postmodernity, Christianity seems to have moved beyond such thinking. God’s grace is bigger than the Church. The focus is now less on our striving as such, and more on how it emerges from our responsiveness, both to God and to others.

In the end, it is all God’s work, and it embraces the whole cosmos. Of course God has entrusted to us the message of that reconciliation. But we have come to think of ourselves less as perfect instruments in the divine hand acting from without, maintaining good religious and social order, and more as participants from within, as people whose engagement with others is a means to our own conversion. The treasure remains, but in earthenware vessels. It has become clearer that the overwhelming power comes, not from us, but from God.