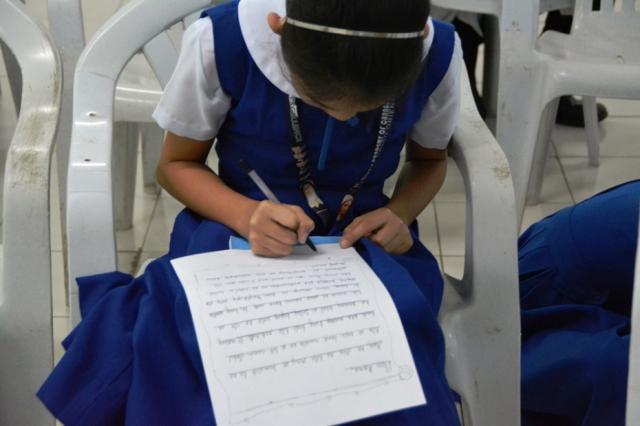

This student, who lives with her grandmother, is one of many, possibly more than a million, children whose mother, father or both parents have gone abroad to work, many as household service workers, nursing professionals, and waiters, bartenders and related hospitality industry workers.

These children are the ones who suffer even as the Philippine government continues to promote labour migration because the dollar remittances of OFWs are helping to keep the Philippine economy afloat.

Official figures show a consistent increase in the number of Filipinos travelling abroad to work, many as household service workers, nursing professionals, and waiters, bartenders and related hospitality industry workers. In 2013, there were more than 1.8 million OFWs. In 2014, the number rose to 2.3 million.

OFWs have been dubbed “modern heroes” for their contribution to the Philippine economy and even the Catholic Church in the Philippines has created annual awards such as “Model OFW Parent”, “Model Son of OFW” and “Model Daughter of OFW”. The UGAT Foundation of the Philippine Jesuit Province is directly involved in scouting for these “modern heroes” for “Bayaning Pilipino Awards” (Filipino Hero Awards), an annual award given by a major Philippine television network.

However, until recently, little had been done to address the impact of labour migration on the families of OFWs. For example, in 2011, the Episcopal Commission on Migrants and Itinerant Peoples (ECMI) found that there was no pastoral programme to speak of in almost all the 15 dioceses in the Visayas in Central Philippines.

The Catholic Church has begun providing pastoral care to OFWs and their families. From August 5 to 7, 2015, the Diocese of Malaybalay in Mindanao invited UGAT Foundation to facilitate a three-day seminar-workshop on Basic Counselling for Migrants for all its Family Life Apostolate workers. The priest-in-charge of the newly created Commission on Migrants in the Diocese of Malaybalay believes its creation is long overdue, considering the real need in the diocese. Almost 170 church workers had wanted to attend but only half the number could be accommodated.

The workshop was divided into four parts – presentation of the basic counselling skills; awareness and appreciation of the person of the counsellor; presentation and appreciation of the psycho-social profile of the OFWs and their families; and presentation and simulation of some counselling interventions. The participants realised that what they have been doing all this time was advising, and not counselling. They found counselling difficult but they wanted to learn because they wanted to help.

The UGAT team comprising Fr Archie Carampatan SJ and Miss Karen Teves also conducted seminar-workshops in Davao Oriental, also in Mindanao, for teachers and students of three high schools run by the Religious of the Virgin Mary (RVM sisters). The teachers unanimously said that the Basic Counselling for Migrants workshop provided them with inputs and activities that expanded their understanding of the psycho-social dynamics of their students who are children of OFWs. They opined that what they learnt could also be used with students who are not children of OFWs.

This is just the beginning. Recognising that there is no stopping labour migration in the Philippines, the UGAT Foundation is committed to finding ways to empower migrant workers and their families by providing psycho-social interventions, especially in areas not reached by the government or other Church agencies.