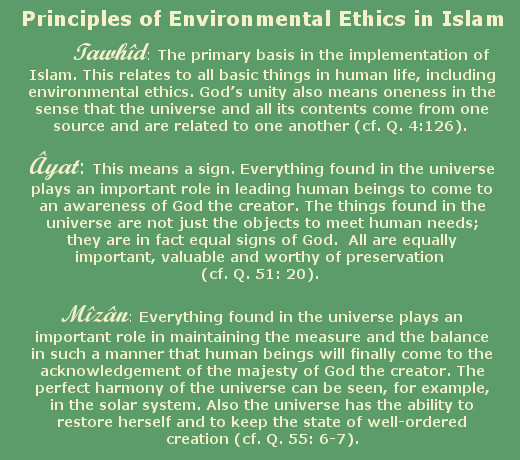

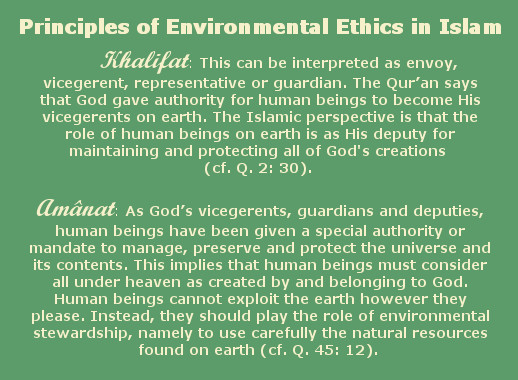

The environmental problems we face today are complex and the Church’s concern is shared by other faiths. In Islam, for example, we can find some principles of environmental ethics that deal with nature and creation. These principles are: tawhîd (God’s unity), âyat (sign of God’s presence), mîzân (balance), khalifat (God’s vicegerent) and amânat (trust).

The environmental problems we face today are complex and the Church’s concern is shared by other faiths. In Islam, for example, we can find some principles of environmental ethics that deal with nature and creation. These principles are: tawhîd (God’s unity), âyat (sign of God’s presence), mîzân (balance), khalifat (God’s vicegerent) and amânat (trust).

These principles have been applied in the light of Islamic environmental jurisprudence on three levels: (1) to be aware of the role of human beings as God’s servants and God’s vicegerents (ta‘abbud), (2) to understand what becomes their responsibility in a rational manner (ta‘aqqul), and (3) to take care or to steward the universe and its contents in such a manner that it becomes the habitual practice of virtue and morality (takhalluq).

How are these put into practice? Islamic regions of former times had regulations for nature and wildlife conservation. Two of these are the himâ and the harîm. Himâ lends itself to the setting up of conservation zones by a community or the state to protect land or species of flora and fauna. Harîm enables the establishment of inviolable zones usually for the protection of watercourses. These regulations include the idea that some meadows and forests were intended for people to go to at certain times only, such as during prolonged dry periods.

For some Muslims, the environmental crisis that negatively affects the quality of the human condition must be tackled as a spiritual crisis.

On this point, we may recall what Pope Francis says in Laudato si’ concerning the argument of a Muslim Sufi, ‘Alî al-Khawaṣṣ, that “one needs not to put too much distance between the creatures of the world and the interior experience of God”. In endnote 159 of Chapter 6, is a quote from al-Khawaṣṣ that reads, “There is a subtle mystery in each of the movements and sounds of this world. The initiate will capture what is being said when the wind blows, the trees sway, water flows, flies buzz, doors creak, birds sing, or in the sound of strings or flutes, the sighs of the sick, the groans of the afflicted …”

At the practical level, attention to the environment and sustainability, including the implementation of green policies, is being developed through education in the Islamic boarding school (pesantren). In Garut, West Java, Indonesia, for example, the al-Thariq Pesantren has based its learning process on “agro ecology”. Students are invited to take care of the ecosystem by paying attention to the surrounding environment and learning about farming.

At the practical level, attention to the environment and sustainability, including the implementation of green policies, is being developed through education in the Islamic boarding school (pesantren). In Garut, West Java, Indonesia, for example, the al-Thariq Pesantren has based its learning process on “agro ecology”. Students are invited to take care of the ecosystem by paying attention to the surrounding environment and learning about farming.

Established in 2009, the al-Thariq Pesantren was designed around the concept of family. It considers first the types of food needed to meet the nutritional needs of all the people living in the pesantren and of their families. Its land area of about 7500 m2 is divided into zones such as fields for rice and other food crops, orchards, and areas for rearing livestock. The members of the pesantren and their families eat what is produced according to availability so they cannot rely on only one type of food. Only when the crops are plentiful, do they consider selling them.

This pesantren is where the immersion experience for the participants of Asia Pacific Theological Encounter Programme (APTEP 2016) will take place.

By Fr Heru Prakosa SJ, JCAP Coordinator for Dialogue with Islam

In August 2016, the Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacific will be convening a multi-sector meeting titled “A call to dialogue on sustainability of life in the ASEAN context” in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. In the run up to this, we are publishing stories on sustainability as it relates to one of the nine participating sectors – Dialogue with Buddhism, Dialogue with Islam, Indigenous Ministry, Social Apostolate, Migration, Reconciliation with Creation, Higher Education, and Basic Education and Formation.

Related stories:

Registration opens for the JCAP conference on sustainability

Converging to dialogue on sustainability of life