How do the children cope with the absence of one or both parents? How are these children perceived by a society that still values traditional family and gender roles? To what extent does migration change the idea of child welfare or parenthood?

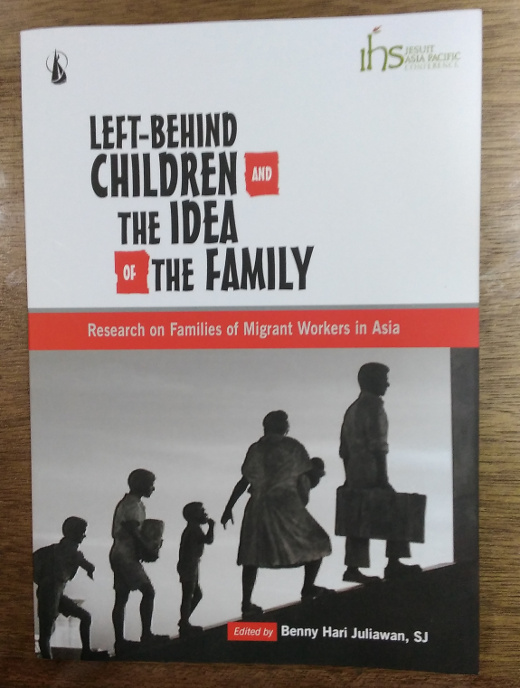

These are some of the questions explored in a new book published by the Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacific (JCAP) Migration Network which comprises of five Jesuit works namely Tokyo Migrants’ Desk, Yiutsari in Seoul, UGAT Foundation in Manila, Rerum Novarum Centre in Taipei, and Sahabat Insan in Jakarta, and the office of the Vietnamese Episcopal Commission for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People.

Migration is a major political, economic, social and cultural concern in Asia Pacific. China, Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia are among the world’s top 25 suppliers of migrants, while Hong Kong, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand are among the top 25 countries in the world with the highest immigration rates.

In 2010, the Jesuit Conference made migration a common priority in social actions, and the JCAP migration network was established in 2014 to facilitate better collaboration among individuals and institutions working with migrant workers.

“Migration has created the notion of transnational families, in which activities that are associated with parent-child relationships are now organised across national boundaries,” said Fr Benny Hari Juliawan SJ, JCAP Secretary for Social Ministries and Coordinator for Migration and editor of the book.

“Research was never a strong point despite their deep and faithful encounter with migrant workers,” said Fr Juliawan. “That is why research became an early focus of the network.”

Each institution adopted their own methods in commissioning the research. Some advertised a call for paper, while the others appointed researchers either in-house or in collaboration with other organisations or individuals.

The article from the Philippines examines the relationship between children and their fathers who become their main carer since the majority of Filipino migrant workers are female, while the article from Indonesia looks at how the children cope with absent parents. Both articles highlight the intergenerational relationships between children and their grandmother, mother and father that form the core of a transnational family.

In host countries such as Japan and Taiwan, the issue of transnational families plays out differently. The story from Japan offers an insight into the hardship endured by children of migrant workers who are brought into the country under strict conditions. The article from Taiwan investigates how macro factors (Taiwanese laws) and micro conditions (gender, age) as well as moderating mechanisms (Information and Communication Technologies and remittances) affect the care arrangement of overseas Filipino workers for their children.

The article from Vietnam offers a different perspective by looking into the lives of child workers in Ho Chi Min City. It presents the result of a small survey that identifies the material and emotional environments of these child workers. Their deprivation has serious consequences on their wellbeing and psychological development.

The collection of articles in the book shows the changing nature of many families in Asia given the surge in people migrating for work. While families are quick to find new ways albeit with struggles, governments have been slow in adapting to the new environment.

“Their main concern is still overwhelmingly economic and limited to facilitating the flow of labour demand and supply across borders,” said Fr Juliawan. “This publication hopefully sheds light on different, more human, dimensions of migration, and encourages appropriate attitudes and policies.”

Download the book here.