This meeting has been held every year since 2015. However, the outbreak of the pandemic halted physical meetings between the two countries. It has been less than a month since Japan resumed visa-free travel. No visa, no quarantine, and no PCR test. The timing couldn’t have been better. Thus, it was a blessing when the long-awaited reunion of 15 participants began at the Museum of the 26 Martyrs of Japan on All Saints’ Day.

The route included visits to the Oka Masaharu memorial Nagasaki peace museum, Nagasaki atomic bomb museum, the Nagasaki peace park, remains of Mitsubishi weapons sumiyoshi tunnel factory, Oura cathedral, the Gunkanjima museum, cemetery of the nameless, hidden Christian sites in Sotome, Endo Shusaku literary museum, Karematsu shrine, Hongouchi Lourdes, and Saint Kolbe memorial museum. That the pilgrimage was held in November, a special month to remember and pray for those who have died, made visiting those places to learn about the missionaries and martyrs in Japanese Catholic history more meaningful, especially as we reflected on the wounds of the war.

As we contemplated the reconciliation between Korea and Japan, our group had special meetings with Korean missionaries in Nagasaki. Priests who came to Japan as missionaries from Korea gave a special guided tour to our Korean companions. The missionary work and the stories of hidden Christians during the persecutions made me think of the Catholic church in North Korea. In the past, some Japanese Catholic priests visited Changchung Cathedral in Pyongyang, and I believe there are many ways for the Japanese church to play an important role in reconciliation and peace on the Korean Peninsula.

We were introduced to many deaths in Nagasaki caused by the Catholic persecution, the atomic bomb, and the forced labour of Koreans in coal mines to name a few. I am not a big fan of “dark tourism” that involves travel to places historically associated with death and tragedy. This is because detailed explanations of violence can run the risk of turning empathy into secondary trauma. How can a person take so many lives like that? It also risks demonising certain groups of people as perpetrators. However, the courage to walk the way of the cross together is also essential on the way to reconciliation, and the memories of those who gave their lives encourage us to continue our peace-building activities.

Japan and Korea share a history of persecution and war. What do we take away from the deaths? Is it the torture or execution method? The causes of persecution? The war damage? The accountability?

How about the courage and love that can be found in the images of the martyrs who happily proclaimed the Gospel even in the face of death?

Korea and Japan also share memories of natural disasters and tragedies. High suicide rates, poverty, and many social problems are common to the two countries. What is needed to heal this trauma in our society, which has suddenly faced many deaths, such as the Itaewon Halloween crowd crush? Sometimes, it feels like we can only hear voices full of sadness, loss, yearning for the punishment of whoever is made the scapegoat. We confess that we forgive those who trespass against us but it is hard to hear voices of forgiveness that accept death peacefully in our society.

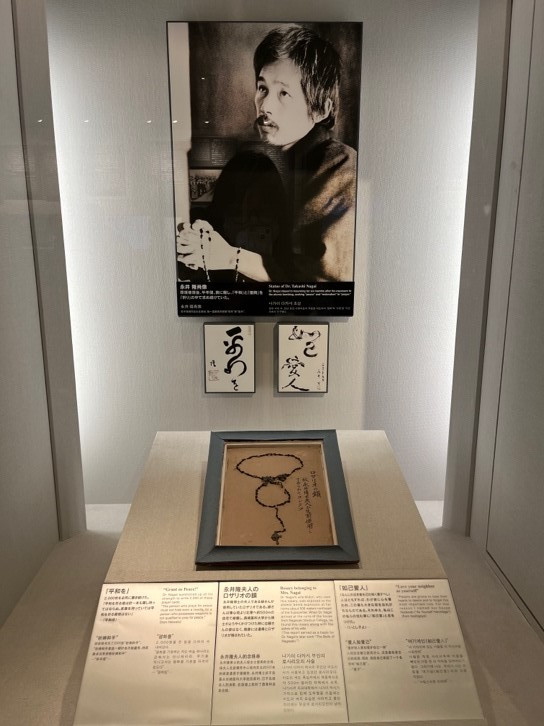

In the corner of the Nagasaki atomic bomb museum there is a picture of a man praying the rosary. For some reason, the image gave me great consolation. Rather than focusing on the history of conflict, don’t we have to learn the history of healing, forgiveness, and reconciliation? We can share our wounds and heal together.

After the pilgrimage, I returned to Tokyo and bought a book titled, A Song for Nagasaki, to learn more about Nagai Takashi, a survivor of the atomic bomb and a convert to Catholicism. He once said: “Love everyone and trust his providence, and you will find peace. I have tried it and can assure you it is so.” I was moved to read how he prayed for the end of the Korean War until the moment he died in 1951. As I imagined the people of Nagasaki praying the Angelus at the sound of the bell, I was filled with new hope and love to continue to walk the path of reconciliation between Korea and Japan.