For 75 years, the Institute of Social Order (ISO), known to be one of the oldest non-governmental organisations in the Philippines, has played a vital role in the formation of civil society organisations, championing laws and policies aimed at improving the lives of the poor and marginalised sectors of society, while being guided by the social teachings of the Catholic Church in promoting a faith that does justice.

ISO’s engagement in social justice began long before its founding in 1947. In the early 1900s, the Philippine Catholic church was grappling with its role in the country’s social transformation. In response to Pope Pius XI’s encyclical, Quadragesimo Anno, in 1931, which called for the reconstruction of social order, the Jesuits founded La Ignaciana Retreat House in June 1932 to promote labour-management collaboration as a countermeasure against the spread of communism in the Philippines. It organised workingmen for social action and conducted recollections for various professions, while Catholic action volunteers assisted in educating workers on their rights and duties. These efforts were broadcast on the “Catholic Hour” radio programme under the direction of Fr Russell Sullivan SJ. La Ignaciana also worked to persuade landowners to redistribute their lands to rural peasants and establish independent peasant proprietorships. However, World War II disrupted these efforts.

In 1946, Fr Walter B Hogan SJ was instructed by his superior, Fr Leo Cullum SJ, to put the papal encyclical into practice. He and his former student, Juan Tan, immersed themselves in the labour movement to understand the problems and sentiments of labourers and discuss the social teachings of the church within their context. They gave talks and lectures on labourer’s rights and labour unions to persuade businessmen to voluntarily improve their workers’ welfare. Fr Hogan came up with the idea of establishing the Institute of Social Order (ISO) to build on the initial efforts of La Ignaciana Retreat House and bring the church’s teachings on social problems to people who were in the position to restructure society. In 1947, ISO was formally established, making it the first of the “pioneer” NGOs in the Philippines.

Despite its imposing name, ISO was initially composed of only two men–Fr Hogan and Mr Tan. They conducted seminars and night classes on unions, social encyclicals, and public speaking for workers in their small office in Padre Faura, Manila. As other Jesuits came and with student volunteers from the Ateneo de Manila University, the Institute offered formal labour education programmes, conducted social research, engaged in labour dispute arbitration, and provided advisory assistance to social organisations and institutes.

Finding no labour organisation to work with in guiding workers’ movements along Christian doctrines, Fr Hogan and Mr Tan established the Federation of Free Workers (FFW), with Mr Tan as its first president. FFW focused on trade-union freedom, lobbying for labour laws, and collective bargaining. ISO publicised FFW’s work and spread its Christian principles. In 1956, an FFW-affiliated labour union called USTELA staged a strike, which resulted in Fr Hogan’s exile to Hong Kong. However, Fr Gaston Duchesneau SJ and Fr Arthur Weiss SJ continued the ISO’s programmes and extended assistance to other labour organisations.

In 1961, Pope John XXIII released the encyclical Mater et Magistra, which emphasised the church’s role in addressing rural conditions by providing services to rural communities, promoting economic development, and recognising the need for citizens of less developed countries to take responsibility for their own development. Inspired by this document, Fr Hogan suggested the creation of a credit union to help poor residents. With technical advice from Fr Duchesneau, a group of young middle-class professionals from San Dionisio, Paranaque organised the San Dionisio Credit Cooperative Union (SDCCU) in 1962 with an initial capital of Php 328 (about US$6). Since then, the SDCCU has grown to become one of the most successful cooperatives in the country. Simultaneously, ISO initiated the introduction of cooperativism in the far-flung communities of Jala-jala and Talim Islands.

The years that followed saw significant changes in the socio-political scene in the Philippines, with students becoming more politically active and Ferdinand Marcos being elected president in 1965. Changes were also happening in the Catholic hierarchy. The influence of Latin American liberation theology was slowly seeping through the teachings of the Catholic church. Vatican II signalled the church’s more lenient stance on socialism and urged Catholics to work for social justice. These changes had a significant impact on the Philippine church and the Society of Jesus. In 1965, the Committee for Development of Socio-Economic Life in Asia (SELA) was established, leading to the establishment of Catholic social action centres in many parishes and the National Secretariat for Social Action. During this period, ISO continued its training and education programmes for the labour and peasant sectors and expanded its curriculum to include a national situationer, liberation theology, and community organising, with many emerging leaders of the NGO movement being exposed to social activism through ISO.

ISO began working with the urban poor through community organising, but this was disrupted by the declaration of Martial Law in 1972, leading to the capture, torture, and killing of many individuals–including some Jesuits–involved in social activism. During this time, General Congregation 32 issued Decree 4, which mandated all Jesuit provinces worldwide to undertake the “service of faith, of which the promotion of justice is an absolute requirement”.

In response, ISO shifted its focus from training and education to community organising and establishing sectoral units. It reconstituted itself into La Ignaciana Apostolic Centre (LIAC) and was heavily involved in the protest movement after the assassination of opposition leader Ninoy Aquino Jr in 1983. LIAC mobilised participation among labour sectors, urban poor, and peasant groups, and emphasised active non-violence to ensure peaceful protests. ISO continued to contribute to the organised response to Cardinal Sin’s call for support during the 1986 EDSA Revolution.

ISO then concentrated its efforts on social development, collaborating with other NGOs and engaging in grassroots education and training interventions. However, in the 1990s, ISO questioned the relevance of its vision and mission, leading to a transformation towards becoming a professional social development institution now based at the Ateneo campus in Quezon City. It adopted a multi-year programme planning cycle and added the women’s sector as its target clientele. The organisation also introduced four auxiliary programmes to address critical areas of work for NGOs during the post-EDSA period: Advocacy and Electoral Programmes, Social Entrepreneurship Programme, Development Communication Programme, and Data Base and Library Services Programme.

ISO’s grassroots-level activities achieved success in advocating for national policies to address the basic needs of its partner sectors. For instance, ISO’s Urban Poor Programme facilitated the development of a federation of urban poor groups in Pasay, Metro Manila, which played a crucial role in passing the Urban Development and Housing Act of 1992 and continues to lobby for laws that meet the needs of the sector. ISO’s approach gave grassroots leaders a chance to enter electoral politics, but it did not produce the expected results, though it provided valuable experience for future actions, and showed that many politically-motivated programmes were no longer effective.

In 1992, ISO underwent a transformation towards social development and intermediary functions, clarifying its contributions to the Society of Jesus Social Apostolate’s faith and justice mission. It focused on empowering basic sectors, promoting sustainable, participatory and equitable development, and transforming unjust traditional structures of power.

ISO developed three strategies to address social problems faced by disadvantaged Filipinos: disaster preparedness and rehabilitation, development management, and empowerment. Organisational systems and procedures were established to enhance ISO’s capabilities. However, internal tensions arose due to community organisers who refused to give up the political aspect of their work.

In 1994, Fr Renato Ocampo SJ led ISO in diversifying its funding sources by consulting with private corporate foundations. ISO also established a research unit to attract new personnel with specialised skills. After Fr Ocampo’s death, a lay director was appointed, and the focus on internal organisational changes and professionalisation continued. An evaluation of ISO’s programmes showed that the organisations and federations established by ISO still existed but no longer had mass bases.

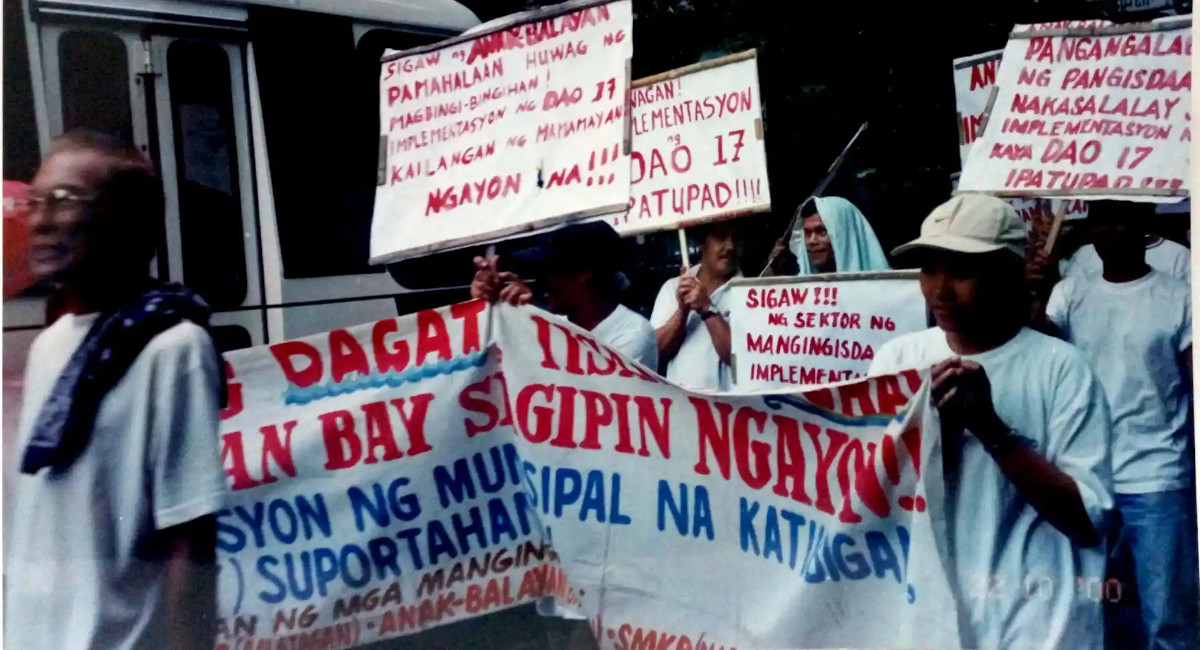

ISO changed its strategy to focus on solid community organising and adopted an integrated area development approach targeting the “poorest of the poor” who received limited assistance from the government, church, and non-governmental organisations. Partnering with social action centres and local government units, they started working with municipal fishers, who were the poorest sector in the 1990s and lobbied for the Philippine Fisheries Code of the Philippines in 1998, and subsequently Republic Act 10654 in 2015, which imposed higher penalties on illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing.

The Institute of Social Order has a long history of promoting social development and social apostolate through community-based approaches to coastal resource management, sustainable development, and empowering fishers to participate in local governance. It has emphasised the importance of participatory research, community organising, capacity building, networking and advocacy, environmental protection, livelihood development, climate adaptation, and youth development. Despite facing challenges, ISO remains committed to its mission and has made a significant impact on the Philippines’ social development. ISO’s faith-based approach has guided its work, allowing it to uphold its mission and promote a faith that does justice.

This article was first published in The Jesuits in Asia Pacific 2023 magazine.