During his tertianship, Indonesian Jesuit Christoporus “Tito” Aria chose Apu Palamguwan Cultural Education Center for his two-week elective mission. He wanted to learn about the use of mother tongue in an elementary school for indigenous people. He shares his experience.

Actually I am not so interested in forestry, even though it is an important thing to do. I am interested in education, especially from elementary until high school. In Indonesia, we have 12 years for lower grade education. Six years for elementary, three years for junior high school, three years for senior high school. In this system, a student who enters the high school must be well educated. Off course they do not have to learn how to read, how to write and how to count; they have already done in Bahasa Indonesia in the big cities.

Before I went to the Philippines for my tertianship, I was working in Adhi Luhur High School in Nabire, Papua, Indonesia. Every year, when we receive new students we still find those who cannot do simple counting, who cannot read and write easily in our national language, Bahasa Indonesia. Usually they came from hinterland, from the mountain area. Why? Because their basic education was not well done. Is it because they do not understand the language, Bahasa Indonesia? Or because of something else?

My early interview with some students in Adhi Luhur, Papua, Indonesia

As I looked back, I remember two interviews with the students who graduated from our school. There was a young girl (I forgot her name) from Mee tribe. There is some sub tribe in Mee tribe that has a different dialect or language. In elementary, in her village, she had to struggle with Bahasa Indonesia. When she moved to another village to continue her study in junior high school, she find it difficult to learn another Papuan language, which was different from her language, plus English as a subject. After she moved to Nabire, to continue her study in our High School, she had to improve her knowledge through Bahasa Indonesia.

Another student, named Siprianus Bunay, of Mee tribe. He told me that when he was in elementary, in his village, he did not understand Bahasa Indonesia. When his teacher taught Bahasa Indonesia he just memorized it. After the class, he repeated what he heard. Sometimes he repeated with a loud voice in the forest, where he collected some branches for fuel for cooking. And during the exam, he could answer the questions, but still, did not understand what he had written.

From these two examples, I am now thinking about the use of their mother tongue language, as a way to explain first the subject and not just teach direct in Bahasa Indonesia. Is it true that using their mother tongue language will help them?

APC, the school with multi‐lingual education method

When I heard about APC (Apu Palamguwan Cultural Education Center), suddenly something came up into my mind. Is it the answer? Maybe.

For the last mission in our tertianship, we have to make our elective mission. I chose to go to APC in Bendum, Bukidnon Province from 2‐18 February 2011. My mission was only one, to know about the use of mother tongue in an elementary school for indigenous people.

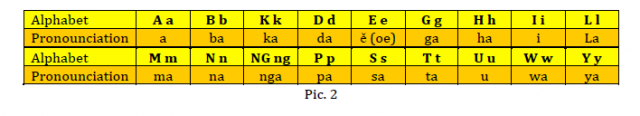

I figured out the language situation in Bendum to be like this:

I figured out the language situation in Bendum to be like this:

From this chart, I knew that the students in APC have to learn at least 4 languages, which is not easy.

In my observation in all off the classes (from kindergarten until grade 6) I found that when the students have to talk or answer some question, they could speak easily in Pulangiyen. They actually learn something in this way and not just mouth it in an unfamiliar language.

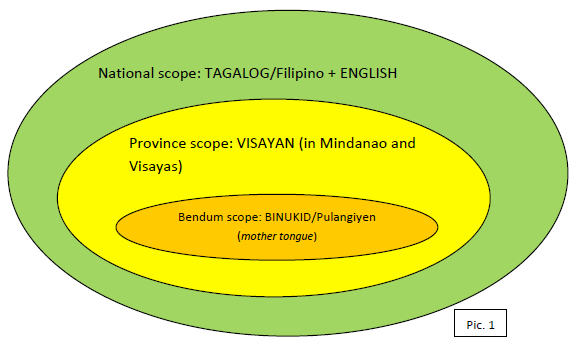

The Pulangiyen alphabet

I was amazed that the Pulangiyen alphabet has differences with the Roman alphabet in pronunciation of the 18 letters.

The students have to learn this alphabet from the beginning, in kindergarten. At grade 3, they just started to learn the Roman alphabet. On Picture 1, we see that Visayan is spoken in the Bendum area. Many of the migrants are from the island of Bohol so the children informally learn from their neighbor’s language the other alphabet.

Using a good Pulangiyen in conversation

When I attended the English class in grade 6, I had another experience. The teacher is a pure Pulangiyen, Cheche Sinhayan. At first, the students have to read the English story. Then the students translate the story in Pulangiyen, sentence by sentence. What happened? Sometimes the student still use the English word because it is more familiar to them. For example, for the word “frog”: when the student wanted to say this word in Pulangiyen, he/she forgot and used the word “frog”. In Pulangiyen it is bakbak. When this happened, Cheche will stop and ask the student to use the Pulangiyen word.

There were two things that surprised me. First, I never liked this in my school, long time ago where we have to translate the English word into our national language, Bahasa Indonesia. It is very difficult to translate English into my mother tongue, Javanese language. I have to think twice, translate it to Bahasa Indonesia and then to Javanese language.

Second, what Cheche was doing was to be consistent in using a language. The message was: if you use Pulangiyen, please use it purely, and do not mix it with another language. Off course, in some cases there is a difficulty to translate some word to Pulangiyen, for instance in Science subject. Cheche said to me that sometimes, teachers are not also consistent in using Pulangiyen in class; they mix it with another language. Even in their textbook, Magkinanau kuy(let’s learn), which is written in Pulangiyen, the consonant “r” which is not part of the alphabet can be found.

Speaking Pulangiyen is not enough

Aijen Linantad, 16 years old, 4th year in High School, is one of the APC scholars. When I interviewed her, she said that she was proud of her culture. The reason was because she could speak Pulangiyen. But when she entered APC she knew that it was not enough. She must know the other part of her culture. In APC she learned a lot about Pulangiyen culture, like dance, folklore, the structure of the community, the role of datu, the social system in community etc.

When I joined the English class in grade 4, the teacher, Nay Jonah, showed some drawing. When she asked the student about this drawing, most of them could easily explain it, with their English. Why? Because the drawing was about their lively culture; it was about the story of their datu doing something, just like in their daily life.

Doing multilingual education (MLE) is not about just using mother tongue

From this experience in APC, I noticed that using the MLE method is not just about making a translation into our mother tongue or speaking our mother tongue. Doing MLE means using our culture in our education and being conceptually grounded in it. For the country that has only one culture, with one mother tongue, it is not hard to do this. But for countries that have many languages, many cultures, and many mother tongues such as Indonesia (700 languages), it is not easy to do this. It cannot be done from the top down but rather from the community up. To learn in the mother tongue is to give strong basis for learning the national language.

We need a national language to bridge the communication with local cultures. But if we are not aware, sometimes the national language kills the mother tongue as well as the local peoples ability to engage according to their capacity. And if there is no mother tongue, there will be no future for that culture and no way of belonging to a society.