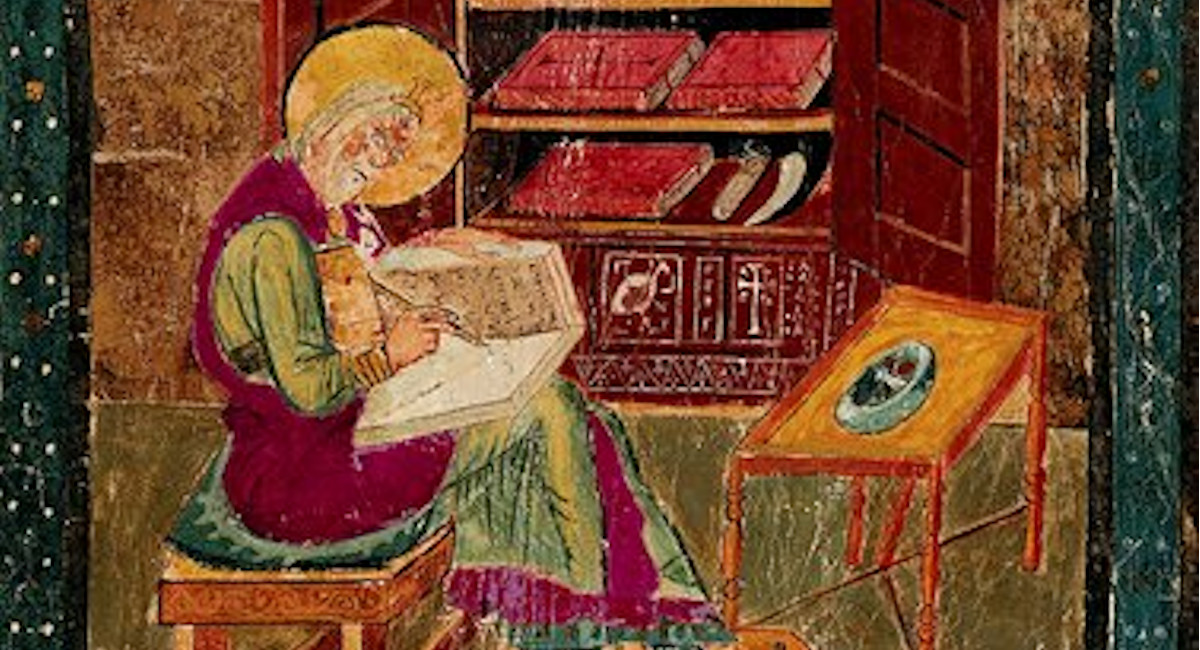

An image on the cover of The Oxford Handbook of the Latin Bible published by the Oxford University Press

Filipino Jesuit priest Fr Oliver Dy is among the international team of contributors for The Oxford Handbook of the Latin Bible, a recently published book edited by Hugh Houghton and written by world-leading experts. It is the first English book to provide a comprehensive treatment of the entire history of the Latin Bible.

Fr Dy is a professor of Systematic Theology at the Loyola School of Theology in Manila, where he also teaches philosophy. He holds an undergraduate degree in Physics, and although he did not pursue this discipline, he tries to integrate its principles into the fields of theology and philosophy where he feels he can be of better service to others.

His involvement in the Oxford Handbook goes back to his time as a graduate student at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium, where he studied under Professor Wim François, an expert in vernacular Bibles in Dutch. During a lecture, Professor François shared a slide of a 16th-century vernacular Bible translation’s cover, which caught Fr Dy’s attention. The translation was described as being based on the Latin Vulgate, which prompted him to question why translators of that time used a Latin translation instead of the original Greek, Hebrew, or Aramaic languages. He was also curious about when the Catholic practice of translating the Bible shifted away from using the Latin Vulgate as the source text.

Years later, Fr Dy defended his doctoral dissertation at the same university, with Professor Houghton serving as one of the panelists. Professor Houghton later invited him to contribute a chapter to the Oxford Handbook based on his dissertation about Catholic vernacular Bibles in German, French, and English published from 1546 to 1965. Professor François, the co-promoter of Fr Dy’s dissertation project, was also invited to co-author the chapter. The questions that Fr Dy had asked years earlier inspired his chapter on the Vernacular Translations of the Latin Bible, which provides answers to some of these questions.

While the book primarily targets academically-inclined readers, Fr Dy hopes that readers take away the implicit philosophy of translation underlying the book chapter.

He says: “How the Bible is translated in the church is indicative of how the church contemporaneously understands itself and its mission. Catholic Bibles at the time of their production can be taken as bearers of ecclesial identity and landmark expressions of the church’s self-understanding at a given historical moment and geographical space.”

He explains that, “Bible translations are shaped and informed by the force of customs in the life of the church” and are “relatable to Church identity as it develops in the course of history. Thus, if contemporary Catholic Bibles are no longer primarily translated from the Latin Vulgate as was claimed to be done in the past, it is because the church today has a different contextual understanding of itself and mission in accord with the present call of the Spirit.”

As a Jesuit, Fr Dy views his involvement in the fields of theology and philosophy as “not simply self-determined” but “as a mission received from above”, through his superiors who represent Jesus the missioner.

“I had no plans to be a theology teacher,” he relates. “As it turned out, I was asked one day, one year after my ordination to the priesthood, if I would want to teach theology at the Loyola School of Theology in the future. I made myself available to this invitation for ministry. Not long after, I was sent to study abroad to get the qualifying academic and ecclesiastical degrees.”

Fr Dy says he is “existentially drawn to search for the truth” and believes that even if he had not been asked to teach theology, he would still naturally pursue the truth through personal reading and engagement with the topics in the field of theology and philosophy.

Referencing the Gospel of John, he says: “I did not choose these fields; they were chosen for me. However it happened, I am thankful and deeply feel that they are the appropriate loci for expressing and pursuing my core desire for the truth.”